Report of the General Meeting of the Alabaster Society

held at the Eighth Alabaster Gathering, 26th April 2008,

in the Guildroom, Hadleigh

Presented by Laraine Hake, Hon. Secretary

Ron Alabaster West opened the meeting explaining that although we do not have a Chairman of the Alabaster

Society, he had, once again, been nominated as the Chairman of the General Meeting. He welcomed those members

who were present and asked for any apologies.

Apologies were recorded from Ian Alabaster (WofW) who was unable to attend at the last minute because of illness,

Evelyn and Les Oram, Rene Alabaster Healey, Oriole Veldhuis and Beryl Neumann. These members all sent their best

wishes for the day. The report of the last General Meeting had been circulated immediately after that event, three

years ago in 2005, and as such was taken as read and correct.

Matters Arising from the 2005 General Meeting:

The General Meeting had then unanimously accepted that the committee should have a mandate to raise the level of

the subscription at some point in the future if it was considered necessary.

No rise was considered necessary by the committee in 2006, but in 2007 it was found that the outgoings had

exceeded our income in the previous financial year so it was decided to increase the subscription to £8 per person

from 1st September 2007. A note to this effect was added to the Spring Chronicle 2007.

A decision was made to start a fund towards paying for research at the College of Arms because we were aware that

there was the possibility of early Alabaster information regarding the award of arms. We raised sufficient money to

have this research carried out by the College of Arms and a report was printed in Chronicle 24. Unfortunately, no new

evidence was found but it was very satisfying to know it had been checked!

Editor of the Journal: Sheelagh and Michael Alabaster agreed to step into the breach (breech?) and we have been

very grateful for the excellent job that has been done. So far five editions of The Chronicle, the flagship of the Society,

have been produced by them.

Website: Once again, an excellent job has been done by Ray. Most of the contacts that have been made to the

Society recently have been as a direct result of the work that Ray has done, including several new members, some of

whom were at the Gathering. Lastly, it was suggested that the table of memorabilia at the Gathering should be more

of a feature in the future, and that it would be of real interest if each contributor was willing to give a two minute

description and explanation of what he or she has brought.

Summary of Committee Meetings: I, as Secretary, presented a summary of the Committee Meetings that have taken

place since 2005:

In April 2006 Sheelagh Alabaster joined us at the Committee Meeting, as editor of the Alabaster Chronicle. It was

decided to treat her as a member of the Committee and put it to the next General Meeting that the editor of the

Chronicle should be treated as a Committee member in future.

We discussed the acquisition of William's book - more on this later..........and we decided to hold the 8th Alabaster

Gathering in Hadleigh, preferably the Guildhall!

May 2007: The Committee decided to increase the subs, as you have already heard, but in future to have the same

level of subs wherever a member lives in the world. The Society received a cheque for £300 for the Alabaster

Research Fund from Tony and Sue. This had come from profit that had been made on their book, Hadleigh and the

Alabaster Family, which they have generously split between Hadleigh Archives and Alabaster Society. Long term

deposit of William's book was discussed - more on this later (again!) The rest of the Committee meeting was used to

discuss plans and arrangements for the 8th Alabaster Gathering - by now already under way! It was decided that the

next committee meeting would not take place at the Gathering, because members did not want to miss out on the

events of the day. We will organize a meeting later this year instead!

Those present at the General Meeting were asked to ratify the Committee's decision to include the editor of the

Chronicle on the Committee in future. This was unanimous. We were reminded that Beryl Neumann is our Australian

representative and it was suggested that we should also have a representative in North America. Robbin Churchill

was asked to become our North American representative and she agreed, despite not knowing what might be

involved...............watch this space!

We moved on to the Secretary's Report: Thank you from me to Sheelagh as Editor of the Chronicle which has been

our main point of contact with members and so very important.

Thank you to Ray as webmaster - hard to believe it is only three years since he took on this role, the website is now

very much a focal point for those outside of the society to find us - a quick show of hands among those present

confirmed that included amongst our number were those who had discovered the Alabaster Society through the

website.

Thank you was said to other members of the committee; to Mick (Michael William) for the excellent display panels he

has produced for this Gathering, to Tony for his support, research and organization; to Joan (not on the committee) for

auditing the accounts, to Peter who organized the committee's visit to Bromley Hall (where Thomas Alabaster wrote

letters to William Cecil in the early 17th century), to Shirley for being theTtreasurer, to Angela for producing the

badges for this Gathering and for hosting committee meetings.

We are now up to member 205, that is families throughout the world, in England, Scotland, Wales, Ireland, Germany,

Netherlands, France, Thailand, Australia, New Zealand, Argentina, United States and Canada.

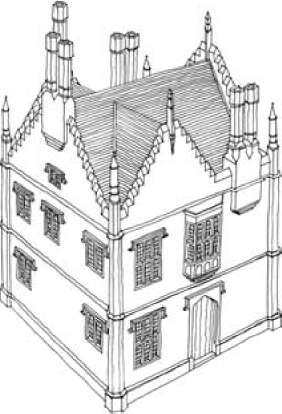

I digressed at this point because it was suggested that not everybody present would know the significance of holding

this Gathering in the Guildroom of the Hadleigh Guildhall.

Sue Andrews, a member of the Alabaster Society and one of the Hadleigh Archivists, was called upon to tell us more.

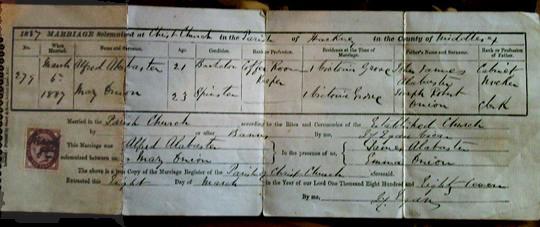

Sue explained that Thomas Alabaster (c1522-1592), n times gt grandfather of all the Alabaster descendants present

(11 x gt in my particular case), was responsible with three other members of the Chief Inhabitants of Hadleigh for

purchasing the Guildhall, for the town, back from the Crown in 1573. This was specifically the actual part of the

Guildhall that we were in today, and the Old Town Hall on the floor above, where we would be eating this evening.

The Chief Inhabitants were later compensated by being given the income from the sale of some cut timber from a

local area that was charity. The Guildhall was immediately turned into the Workhouse which it remained until 1834.

Treasurer's Report Shirley Alabaster presented the accounts to us and apologized that they had not been in the

previous Chronicle, despite having been emailed to Sheelagh...............they had been lost in cyberspace as does

happen on occasion. There were no questions and the accounts were accepted. Shirley did ask that when people paid

online they should make especially sure that they included their membership number as there were many people with

the same surname!

Shirley was able to tell us the exciting news that an anonymous donation to the Society for £2000 had been received

for which we are very, very grateful. A small part of this generous figure, £85, had been spent on the marvelous

family tree on the wall behind us - stretching for more than 40 feet in width!

Election of Officers and Committee The officers of the Society, that is myself as secretary and Shirley Alabaster as

treasurer, were re-elected unopposed as were the rest of the existing members of the committee. The meeting also

agreed that the committee should have the power to co-opt other members, as seen fit in future.

Any Other Business Ron reminded everybody that Sue and Andrew's book, Hadleigh and the Alabaster Family, was

for sale; John Stammers Alabaster had wonderful lead shields of the Alabaster crest for sale; raffle tickets; jewelry

from Alabaster & Wilson could be ordered from Stephen Alabaster; (Stephen said that he had brought along some

examples of the jewellery and that a choice of one piece was being offered as a raffle prize..............and later, I WON

IT, and chose a lovely Alabaster pendant. Thank you, I wear it often). Ron also referred to the memorabilia table and

the wonderful array of items that would be being shown later.

Other items for sale included Alabaster badges and Alabaster binders.

Sheelagh asked that people be careful to use her correct email address and promised that she would always reply

quickly to say an email had been received. She asked, specifically for items on today's Gathering to be sent to her for

the next edition of the Chronicle.

I reported that I had been contacted by the trustees of the Alabaster Charity for our opinion on the suggestion that

the Alabaster Charity should be merged with the Ann Beaumont Charity. We had replied that we understood that this

was a sensible idea but stressed that we would like Alabaster to remain in the title.

I also reported that the trustees of the Hadleigh Feoffment Charity had contacted us and offered us a 20% reduction

in the cost of hiring the Guildhall today and in the future because it was Thomas Alabaster who had involved in

buying it back from the Crown as we heard earlier today. We all agreed that this was a lovely gesture for which we

are very grateful.

Recent developments on our Family Tree

Before we concluded the meeting, I was able to give some feedback on the shape of the tree itself! Firstly, I was able

to refer to where, in my opinion, the William of Woodford branch should fit. Having given it some considerable time

and thought in the past few months my belief is that it is likely that William Alabaster who called himself "of the

parish of Woodford, Essex" at his marriage to Mary Plummer in 1806, was the son of William and Eleanor (nee

Scopes) who married in Messing in 1780. William and Eleanor were certainly living in Leyton, Essex in 1788, not far

from Woodford. This William, the father, is very likely to have been the son of William born 1754, son of William and

Martha Cockrell (Branch I) .................something I hypothesized way back at the very first Gathering in 1990. As

William was the eldest son of William and Martha, this puts William of Woodford firmly as the senior member of

Branch I,

BUT - and this is where there has been an enormous alteration - it appears that Branch I itself is no longer the senior

branch of the Alabaster family tree - this is a fact to which Ron alluded several times during the day, and therein lies

a story.

The Elevation of Branch IV Almost all Alabaster descendants alive today count amongst their ancestors, not only

Thomas of Hadleigh (c1522 -1592) but also his son John (1560-1637) who started the Alabaster Charity, his grandson

Thomas (married 1623) and his gt grandson John (born1624). It is with the offspring of John that we get the first

division of branches, in particular, their two sons, William and John.

John Alabaster = Elizabeth (1624-1700)

William Alabaster = Ann Clarke John Alabaster = Mary Branch I, Branch IIA, IIB, Branch IIIA, IIIB Branch IV

William and John were both born in the mid 17th century, probably during the Commonwealth when parish records

were not kept and so we have no baptismal dates for either of them. However, in earlier days of Alabaster research,

about the time of the first Gathering in 1990, we took William to be the elder and labelled various lines that

descended from him as Branches One, Two and Three; the line that descended from John was labeled Branch Four.

It was only when the giant tree was being produced that I had occasion to query this assumption. The printers had

"mistakenly" put John as the elder which meant that Branch IV was on the extreme left of the tree. However, this did

cause me to look at the evidence a little more closely............

William was married to Ann Clarke in 1682 in Claydon, Suffolk.

We do not have a marriage date for John but, on closer inspection, I realised that his eldest child, John, was baptised

in Campsea Ash in 1678...........which rather indicated an earlier marriage.

Then came the deciding realization.................John Alabaster, born 1624, is very, very likely to have followed the

normal procedure of the time and named his first son after himself, JOHN.

Thus it was that I realised that the elder of Branch IV was senior to those of Branches I, II and III. William of

Woodford's elevation to the senior branch was very short lived. I think it has to be accepted that Branch IV has taken

its rightful place on the more senior, left-hand side of the tree!

With this information, the General Meeting of the Alabaster Society, 2008, was brought to a satisfactory (for some!)

conclusion!

|

Bromley

Hall offers 4,000 sq. ft. of office space for small businesses in the

Poplar area of Tower Hamlets.

Bromley

Hall offers 4,000 sq. ft. of office space for small businesses in the

Poplar area of Tower Hamlets.