Roger Aliblaster of Youghal

by Tony Springall

Pam and I were attending the AGM of the Bristol Record Society to hear the lecture and to collect our copy of the

2009 book, a slim volume of 1080 pages weighing 3½ pounds, called ‘Bristol’s Trade with Ireland and the Continent

1503-1601’(1). The book is predominantly a transcription of many of the 16th century Port of Bristol customs

accounts available at The National Archives.

Now, no one in his or her right mind, or at least not I, would realistically expect to see an Alabaster mentioned in this

book but, as I was rapidly flicking through the book to get its measure, Pam jabbed me in the ribs and said ‘There’s

an Alabaster!’

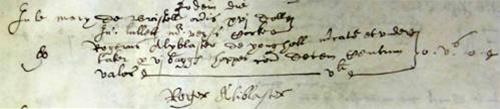

I quickly retraced the pages and, sure enough, there was the following entry [items in square brackets are my

additions]:-

The Mary of Bristol, [burden] 16 tons, John Lullet master, [from Bristol] to Cork, 8th August 1595 Roger Aliblaster of

Youghal, Merchant & Undertaker Ind[igenus – i.e. native] 10 C [hundredweight of] hops [worth] £5 [packaged in] 6

bags

Surely this is Roger the youngest brother of Thomas Alabaster of Hadleigh! This assumption was subsequently proven

by examining the original port books which contain a signature matching other signatures we have of Roger (2). The

signature also proves that Roger was at the port of Bristol on August 8 1595. The transcription is a composite of two

original records, one of which is given below.

Note the small drawing of a clover or shamrock leaf. This is the merchant mark of Roger -

the first time, to my knowledge, we have identified the merchant mark of any Alabaster. Note the small drawing of a clover or shamrock leaf. This is the merchant mark of Roger -

the first time, to my knowledge, we have identified the merchant mark of any Alabaster.

Some of you may have not come across Roger before so a few words about him may be

helpful. Roger Alabaster was the youngest brother of Thomas Alabaster of Hadleigh, his

senior by twenty years. Born in west Norfolk about 1539 to William Alabaster and

Margaret Shaxton, he was largely raised by Margaret and her second husband, Robert

Halman. At some point he followed Thomas to Hadleigh where Thomas was rapidly

making a name, and a fortune, for himself. He married Bridget Winthrop, a daughter of the affluent Winthrop family

in 1567 and by her had 9 children, the most famous of whom was William (1568-1640), the poet and recusant. Unlike

his brother and his Alabaster nephews, Thomas and John, Roger never achieved wealth, or even affluence, with most

of his endeavours falling short of success. He died in 1613 and was buried in St. Margaret’s Church, Westminster.

The Port Book entry is only the fourth reference we have mentioning Roger in connection with Ireland. The other

three are all in the diary of Adam Winthrop, his brother in law. We know that Roger & family bid farewell to Adam

Winthrop at Groton on July 8 1595, when “it thundred and Rained very sore”, to go to Ireland. Adam received a letter

on December 9 the same year from a returning Roger written from Tenby in Wales “concernynge his ill success in his

Irisshe journy". Finally Roger and John Winthrop, Adam’s elder brother, travelled to Ireland together in June the

following year. John Winthrop settled in Ireland but Roger was back in Suffolk before Midsummer 1597.

The Port Book record gives some obvious information but also raises a series of questions and, in addressing these,

interesting insights into Roger’s venture are revealed.

My first thoughts on seeing the transcription were that Roger and his family had travelled to Ireland by boat, probably

from London or, possibly, from Ipswich and that by August 8 Roger had arrived in Youghal and was hard at work

importing goods from England.

Where is Youghal? - I had never heard of the town before. Youghal is an ancient picturesque town in south east

Ireland between today’s better known towns of Cork and Waterford. Until the 18th century, when the increasing size

of ships restricted its suitability, Youghal was the major port of the three towns. Youghal was sacked in 1579 by Irish

rebels and from this rebellion arose attempts to stabilize the area by ‘planting’ English settlers. From 1586 until

1602, Sir Walter Raleigh was the major landowner in the Youghal area and he was Mayor of the town in 1588 and

1599. Edmund Spenser, another major landowner, is considered to have written part of his classic poem, The Faerie

Queen, in the town.

How long would the journey have taken from Hadleigh to Youghal? I investigated Tudor and Stuart journeys along the

English Channel but found very few with reliable times or journey durations - most accounts writing of delays and

favourable or unfavourable winds. Two English colonization voyages, the voyage to Jamestown in 1607 and to New

England in 1630, were helpful. These voyages were held up for considerable periods in the Channel - the 1607

voyage for 6 weeks! However, when these expeditions cleared the Channel they averaged 60 miles per day to their

destinations. At this speed it would take 10 days to sail from London to Youghal or Cork but was this possible along

the Channel? I rang an experienced yachting friend of mine to sound him out and he strongly held that, typically, it

would take significantly longer than this as the wind direction keeps varying along the Channel. This information

appeared to rule out the use of the English Channel route and this was supported by other evidence. First, research

established that Bristol vastly dominated trade and travel to south-east Ireland. Second, examination of 17th century

journeys made by frequent travellers between south-east Ireland and London revealed the exclusive use of the land

route from the West Country to London (3).

How long would the land journey take? Investigation showed that an urgent horseman changing to fresh horses as

necessary could achieve up to six miles per hour, horse travel at a more sustainable pace achieved 3-4 mph, a

carriage pulled by four horses could achieve 30 miles per day but a cart loaded with possessions would be

significantly slower (4). All these speeds are based on real 16th/17th journeys between London and the West

Country, a distance of about 120 miles. Roger and family would have most likely travelled by wagon but otherwise by

carriage. Bristol is 200 miles from Hadleigh which suggests that their journey to Bristol took at least 7 days. If Roger

and family left home promptly on July 8, they could have arrived at Bristol as early as July 15 1595. However it is

more likely that they arrived after July 20.

How long would it have taken to travel from Bristol to south-east Ireland? The duration can be broken into three

elements:

1) Waiting for a suitable boat. Roger’s wait can be estimated from the Port Book. Of the boats listed, only two boats

to Cork or Youghal had goods taxed onboard between the earliest arrival of Roger in Bristol and the taxation of his

hops on August 8 (5). These boats were 'The John of Bristol' which was loaded and taxed on August 5 having arrived

from Youghal on July 17 and ‘The Mary of Bristol’ which had arrived from Cork on July 19 and was taxed for Roger’s

hops on August 8. Two boats were bound for Waterford; ‘The Gift’ which arrived on July 21 and was taxed on

outgoing goods on July 31 and ‘The John of Waterford’ which arrived on July 22 and was taxed on outgoing goods on

August 2. However Waterford is twice as far as Cork from Youghal and it is probable that Roger would have preferred

to wait for a Cork or Youghal boat (however, see 2). The logical choice would have been to travel on ‘The John of

Bristol’ but Roger and family may have arrived too late to obtain passage on that ship or preferred ‘The Mary’ for

some reason. Whatever the reason for their choice, there is evidence, which I will come to later, that Roger, Bridget

and their family did personally travel on ‘The Mary’ with their hops.

2) Waiting for suitable weather conditions. The taxation date of goods on an outgoing boat was not the same as the

departure date of the boat. The date a boat actually sailed was highly dependent on weather conditions. This wait

varied enormously from no wait to a delay in excess of two weeks - even 3 months according to one reference. It is

notable that between July 27 and August 7, inclusive, no incoming boats from any port of origin had their cargoes

taxed at Bristol. Such a long inactive period, although not unique, was exceptional and suggests that bad or windless

weather had stopped all sea voyages coming to the port. It seems reasonable that outgoing boats, including ‘The

John of Bristol’, ‘The Mary’, ‘The Gift’ and ‘The John of Waterford’, would also have been unable to sail during

this period – making the last two boats even less attractive to Roger.

3) Actual travel time. Examination of 17th century sailings shows that in extremely favourable weather the journey

between the West Country and south-east Ireland could take 24 hours but it could take three days, with two days

being most common. As a modern example, my yachting friend took 36 hours in favourable weather to sail from

Kinsale, near Cork, to Padstow, Somerset.

Assuming that Roger personally travelled on ‘The Mary’ rather than ‘The John of Bristol’, we must add a further two

days to his journey to organize and travel the 32 miles from Cork to Youghal.

What is the evidence that Roger travelled on the ‘The Mary’ rather than the ‘The John of Bristol’? It is extremely

rare for Port Books of the period to name passengers as they are solely concerned with the taxation of goods. So it is

no surprise that Roger and his family are not mentioned as travelling on either boat. However, the identification of

Roger as an ‘Undertaker’ provides a clue that they travelled on ‘The Mary’.

‘Undertaker’ in this context is a person who has or has arranged to ‘plant’ himself in the so-called ‘Plantation of

Munster’. Chief Undertakers, such as Edmund Spenser and Sir Walter Raleigh, had been granted thousands of acres

from the Crown in 1586 and were required to parcel out chunks of that land to subordinate undertakers of English

stock. The Crown’s main motive for this was to secure the land against the dispossessed Irish. Many undertakers,

including John Winthrop, Roger’s somewhat disreputable brother-in-law, fulfilled this obligation by fighting against

the Irish in the rebellion of 1598. Sir Walter Raleigh, as one of the Chief Undertakers, was criticized repeatedly for

failing to attract colonists. It appears that Roger was a new Undertaker and almost certainly recruited by John

Winthrop, who left Suffolk for Munster in April 1595.

Why would the custom official record that Roger was an ‘Undertaker’ unless there were tax implications for the

items Roger was transporting on “The Mary”. Roger paid the full tax for his hops so he must have been transporting

other items. There is evidence that colonists were allowed to "export diverse sorts of household stuff, apparel &

other provisions’ . . . . free of duty." (6) Thus by naming Roger as an ‘Undertaker’ the official appears to be

signifying that Roger had personal effects which were being exported tax free. If their ‘household stuff’ was on “The

Mary” then, surely, so were Roger, Bridget, George, John, Thomas and Sara Alabaster. It is possible, of course, that

Roger and family travelled on ‘The John’ leaving their possessions to follow on ‘The Mary’. I know what my choice

would have been, particularly as ‘The John’ was prevented by the weather from sailing significantly earlier than

‘The Mary’.

What sort of boat was 'The Mary`? I searched for Tudor/Stuart merchant boats of around 16 tons but found nothing

convincing although I found many images of much larger boats. Then I realized that I had photos of such a boat

already in my possession. In 1607 three boats: Susan Constant (120 tons), Godspeed (40 tons) and Discovery (20

tons) set out for Virginia to found the colony of Jamestown. The Jamestown - Yorktown Foundation of Virginia owns

replicas of all three boats. No plans for the original ‘Discovery’ survive so the replica design was a composite of

information about merchant boats of this size. As part of the Jamestown 400th anniversary commemorations a new

replica of the ‘Discovery’ was commissioned and the previous replica was given to a specially created English trust.

This replica toured England in 2007 to seek a final resting place in this country and in July it visited the Bristol

Harbour Festival where I took the photograph below. What could be more appropriate as a substitute in our

imagination for ‘The Mary’.

Replica of the 20 ton "Discovery" in Bristol Harbour.

The original sailed to Jamestown in 1607 with 20 souls on board.

Why was Roger taking so many hops to Ireland with him? Five hundredweight seems too much for his personal

consumption. I assume that he was planning to sell them or to brew beer for sale and this is presumably why they

were taxed. However hops quickly become substandard unless they are kept in ideal conditions. This, together with

their large bulk per unit of weight, suggests that he bought them in the Bristol area. Did they deteriorate badly on the

voyage to Ireland and could this have contributed to his problems?

In summary, my opinion is that Roger and his family set out from Suffolk by wagon on Tuesday July 8 to travel the 200

miles to Bristol, arriving there in mid to late July. They found just two boats, ‘The John of Bristol’ and ‘The Mary’

destined for suitable ports but neither was ready to load cargo. For some reason, probably because ‘The John of

Bristol’ was already reserved, Roger settled for ‘The Mary’ but did not load his possessions until Friday August 8,

when the weather permitted sailing. Perhaps he didn’t want to pay tax on the hops earlier than necessary or he

feared for his goods in a stormy harbour. David Lewis, the other merchant using ‘The Mary’, loaded his goods on

August 9 and ‘The Mary’ sailed soon after, arriving at Cork on August 10 or 11. Two days later Roger, Bridget and

their four children would have arrived in Youghal by wagon, eager to view the property they intended to occupy for

the foreseeable future.

Within very few months of his arrival Roger was returning. Clearly something went wrong for the family in Ireland;

maybe the deal struck by John Winthrop fell apart or an atmosphere of rebellion alarmed the family. The letter sent

by Roger from Tenby would have explained the difficulties and sought assistance, possibly a loan, from Adam

Winthrop. It is not certain that the family returned with Roger on this occasion but we know the Irish dream was

never to be realized.

Sources used:

(1). Bristol’s Trade With Ireland And The Continent 1503-1601 by Susan Flavin & Evan T. Jones (eds), BRS 61, 2009.

(2). The National Archives, E190/1131/12 (shown) and E190/1131/10

(3). Life and Letters of the Great Earl of Cork by Dorothea Townshend. 1904; The Lismore Papers of Richard Boyle.

First and “Great” Earl of Cork Vol I part 4, 1886; A history of the life of James, Duke of Ormonde by Thomas Carte

(4). “An Elizabethan Progress" (Sutton Publishing, 1996), Zillah Dovey.

(5). Arrival dates are not given in the Port Book and I am using my best estimate of the arrival date which is the first

taxation date of an incoming boat. Analysis of the Port Book strongly suggests that the preferred practice was to tax

a boat on its arrival day or the day after for Sunday arrivals. For example, there was no taxation on any Sunday but

roughly twice as many boats were taxed on Mondays as other days. This implies that boats continued to arrive on

Sunday and both Sunday and Monday arrivals were usually taxed on Monday.

(6). National Archives’ Information Sheet on Port Books.

|